Post-Bankruptcy PG&E and Investing In Utilities

Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) emerged from bankruptcy in early July. The company was forced to restructure in 2019 under the weight of crippling liabilities stemming from the tragic 2018 “Camp Fire” - the costliest and deadliest wildfire in California’s history caused by some of PG&E’s faulty electrical equipment.

At first glance, the reorganized PG&E looks like a special situation and value investor’s dream because of the lengthy list of catalysts and cheap valuation. Additionally, a slew of prominent value investors own large stakes in PG&E, including Buapost Group, Third Point Management, Appaloosa Management, and others. Also, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway owns one of the largest electric utility companies in the nation – Berkshire Hathaway Energy (formerly MidAmerican Energy). If Buffett is willing to own a utility – shouldn’t every investor consider taking a look?

The stock has all the makings of a special situation whereby one or more catalysts cause a rapid rise in share price. Here I’ll review the potential catalysts and assess the overall quality of the business and investment case.

Catalysts

Upon emerging from bankruptcy PG&E has several blemishes that may hold back the stock in the near-term. These include:

1) PG&E is currently searching for a permanent CEO.

PG&E board member Bill Smith is serving as interim CEO after Bill Johnson stepped down as the company exited bankruptcy. Investors often remain jittery about placing money with companies who are in leadership limbo.

2) The company cannot pay a dividend for several years.

Under the company’s agreement with California, they cannot pay a dividend until they have earned $6.2B of adjusted income. The company estimates this won’t occur until around 2023. Predictable and healthy dividend yields are one of the main perks that attract investors to utilities and PG&E is unlikely to draw from this investor base until a dividend is reinstated. When this does occur, it’s likely that dividend-focused investors, mutual funds, and ETFs will flock to buy the shares.

3) Certain funds are forbid from owning PG&E.

On-trend “ESG” (environmental, social, and corporate governance) focused funds are typically unable to invest in PG&E because of its criminal sentence (the company pled guilty to manslaughter related to the Camp Fire). Also, many funds can’t or won’t hold shares in a company for a period of time after they emerge from bankruptcy.

4) The 90 day post-bankruptcy lockup period ends in September, creating an overhang on the shares.

Large institutional investors that bought shares at a discount as part of the bankruptcy exit-financing package cannot sell their shares for 90 days. Also, the wildfire victims trust, which owns over 20% of the company, has a similar lockup period expiring around the same time. The market may be concerned of a real or perceived risk that a flood of shares will come onto the market in early fall and drive the shares lower.

5) Opaque true earnings power is masked by large “one-time” bankruptcy and Camp Fire related costs.

PG&E has booked massive charges from the bankruptcy proceedings and the aftermath of major wildfires. For 2020 the company projects to incur around $2B of excess costs related to the bankruptcy and wildfire insurance fund contributions, resulting in artificially low profitability. These costs amount to nearly 100% of normalized earnings and make the stock appear extremely expensive in relation to earnings on a trailing GAAP basis. Quantitative-based investors may avoid the stock temporarily until the true earnings power is evident on a GAAP basis.

A reversal in one or more of these dynamics could ignite a rapid rise in the stock price and reward long-term investors for holding through these short-to-medium-term overhangs.

In addition to these issues, PG&E suffers from a major “ick” factor. Who wants to own a company that caused the deadliest wildfire in recent memory and that just went bankrupt? Oftentimes the poor publicity in and of itself is what creates temporary price-to-value discrepancies.

Valuation

These dynamics result in what looks like a cheap stock. Per the company’s bankruptcy filings, they should roughly break even this year on a GAAP basis and earn around $2B before legal and wildfire related expenses. They estimate GAAP earnings of $2.4B by 2024, or $2.9B before special charges.

If management proves correct, the stock trades at about ~9x 2020’s adjusted earnings, roughly half of where their dividend-paying peers trade.

Source: Author, ValueLine Review

The best comp is Edison International (EIX) because it is another pure-play California regulated utility that is also participating in the state's fire insurance fund. If PG&E closes 80% of the peer valuation gap by 2024 (which may be generous given the risks of operating in California and leverage) to trade on par with Edison, and earns $2.4B, shareholders would see a ~17% annual return over four years. Modest further share count dilution seems inevitable (more on that later) so net returns would likely be more like 15%.

Source: Author, company bankruptcy filings

There are numerous uncertainties as to what happens over the next several years that could impact earnings and valuation expectations, such as:

- How will the market handicap the valuation due to the lack of dividends through 2022?

- What if another major wildfire hits and the $21B state fund that is supposed to cap the company’s medium-term liabilities is depleted? There are no plans to replenish the fund when it runs out and shareholders may be asked to pony up again.

- How will investors react to PG&E’s massive debt load? Analysts estimate over 30% of PG&Es cash generated will go towards debt payments.

These are all big unknowns that I don’t have an answer to. With these looming uncertainties, a high-quality base business seems like a must for prudent investors.

Business Quality

For those not familiar with how utilities companies work, a quick review. Because utilities provide a public necessity (electricity) and to incentivize continued investment in a public need, government regulators allow them to operate as local monopolies. In turn, regulators determine a reasonable rate of return that utilities can earn on their capital investments. In the U.S. regulated utilities are permitted to earn ~10% return on equity on the large sums of capital they invest. This is far from extraordinary but should come with high certainty and reasonable growth potential.

In studying PG&E, I thought it would be instructive to go back to the year 2000 and read Buffett’s annual commentary on Berkshire’s utility conglomerate, now known as Berkshire Hathaway Energy (at the time MidAmerican Energy). It might be helpful to compare the investment merits Buffett saw in MidAmerican to what we have today in PG&E to draw some conclusions on the quality of the company.

Buffett’s View on Utilities

In 2000 Buffett was approached by Walter Scott Jr., a Berkshire director who also served on the board of MidAmerican Energy, about investing in MidAmerican.

After reviewing the company’s filings Buffett liked several aspects of the business, including:

- The predictable, recession-resistant, monopolistic stream of earnings electrical utilities provide due to their mission critical nature;

- It provided him a chance to deploy large sums of his growing cash hoard at reasonable rates of return for long periods of time;

- MidAmerican was run by exceptional managers in David Sokol and Greg Abel who had a zeal for efficiency, safety, and service;

- The company was diversified throughout many states, shielding it from adverse actions from any one regulator. They also would have the chance to acquire many more utility companies provided they stayed in the good graces of regulators.

What really stood out to Buffett were the last two points. MidAmerican’s management team was relentlessly focused on cost and safety. At Sokol and Abel’s direction, MidAmerican almost never raised rates for customers. From when BHE acquired its first Iowa utility in 1999 they did not raise rates for 16 years while industry rates increased 44%. They also had an outstanding safety record and never cut corners.

Further, they focused on delivering unwavering reliability to customers. Upon acquiring other utility providers, it was not uncommon for customer satisfaction to skyrocket because of improved reliability due to MidAmerican’s investments and focus.

After Berkshire invested, MidAmerican grew substantially by acquiring utility operators across the country in more than 10 states and aggressively reinvesting into the business. These acquisitions were made possible because of how favorably regulators viewed BHE. As Buffett said in his 2015 shareholder letter (referring to BHE’s unremitting focus on cost, service, and safety):

“Those outstanding performances explain why BHE is welcomed by regulators when it proposes to buy a utility in their jurisdiction. The regulators know the company will run an efficient, safe, and reliable operation and also arrive with unlimited capital to fund whatever projects makes sense”

Also, because BHE reinvests so heavily in the business, doesn’t pay dividends, and is so well capitalized, they can fund a portion of the business with extremely low-cost and non-recourse (to Berkshire) debt, which enhances returns and minimizes risk.

In summary, while investing in a capital-intensive and moderate return business is not Buffett’s preferred opportunity, he liked what he saw in MidAmerican. From the 2005 letter Buffett said:

“Take care of your customer, and the regulator – your customer’s representative – will take care of you. Good behavior by each party begets good behavior in return.”

This good behavior has allowed them to earn respectable returns on large sums of money that otherwise may be sitting in Buffett’s ever-growing cash pile. Berkshire’s share of after-tax earnings in its energy business has grown from $109M in 2000 to $781M in 2019, for a 10% annual growth rate. This segment has created tremendous risk-adjusted value over two decades for shareholders.

How does PG&E Stack Up?

PG&E certainly possesses some of the desirable traits that all utilities enjoy. They are a monopoly in the northern two-thirds of California with the opportunity to deploy large amounts of capital at a reasonable rate of return. They receive a recession-resistant stream of earnings with decent visibility into the future. However, in the most critical area that Buffett highlighted in MidAmerican – regulatory risk - PG&E falls well short.

First and foremost, the company neglected to maintain its equipment for years, skimping on safety checks and routine maintenance that contributed to the most costly and deadly fire in California’s history. This, of course, has landed PG&E squarely in the regulatory doghouse, with government-imposed limitations on dividends, huge catch-up capital expenditure requirements, mandatory contributions to a wildfire cost-coverage fund, and uncertainty abound. These costs led to bankruptcy and the company emerging with substantially more debt – roughly $40B - than before.

Second, PG&E has the misfortune of operating in California, not exactly a business-friendly state. Last year was actually the second time in as many decades that PG&E has declared bankruptcy, and the first can largely be attributed to hard-headed California regulators, which you can read about here. PG&E also lacks any diversity in regulatory exposure given it does business exclusively in California, compared to the variety of states that MidAmerican services.

In short, the regulators are the most powerful extrinsic factor for PG&E and are unlikely to do them many favors or allow them to acquire other utilities anytime soon.

The other aspect I struggle to overcome is the lack of free cash flow in most utilities. PG&E does not currently, or expect to in the future, generate free cash flow.

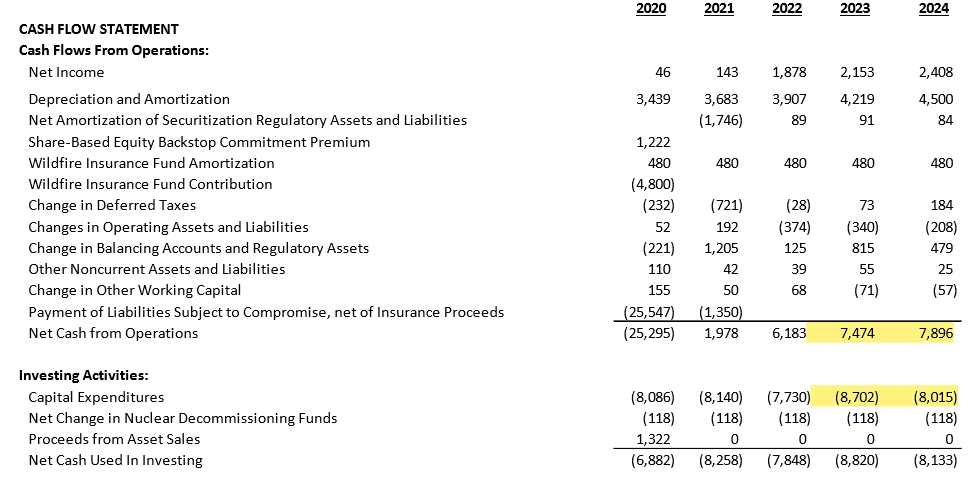

Source: company projections, bankruptcy filings

Highlighted above, even in a “normalized state” in 2023 and 2024, operating cash flow is projected to be $7.5-$8B against massive capex spending of $8-$8.7B.

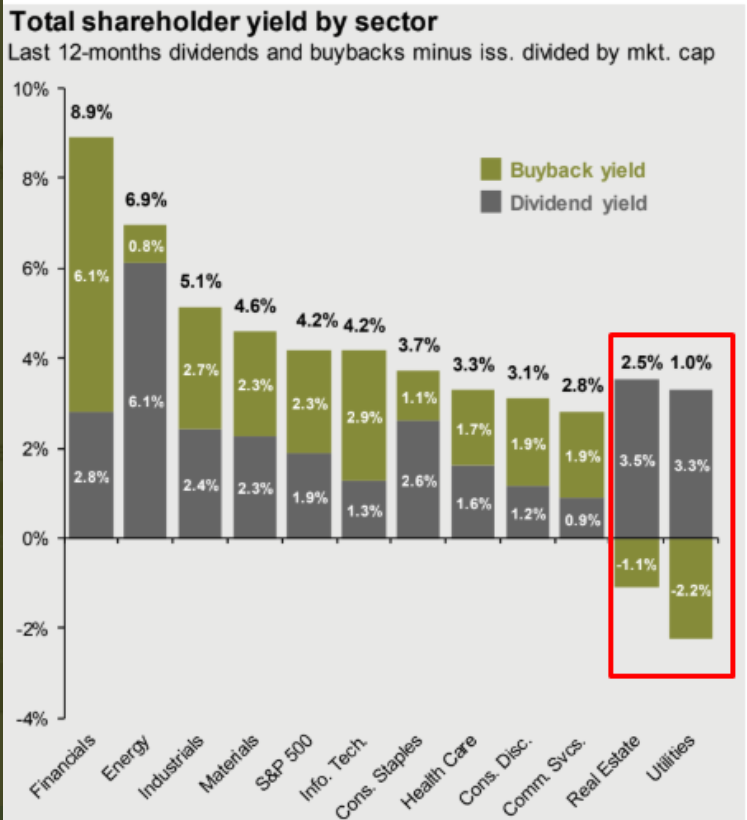

Most utilities fund their dividends through debt and share issuances, diluting returns for current equity holders. As Vitaliy Katsenelson pointed out a few weeks ago in the picture to the right, utilities true “shareholder yield” is a puny 1%, which he referred to as a more or less of a scam. This is hardly a winning formula for investors over the long term.

I realize the counterpoint to this is utilities receive a “guaranteed” return on growth capital investments. The thought is they could, in theory, pare back growth capex and generate free cash flow. The problem in PG&E’s case is they clearly were not even meeting their maintenance capex requirements before the Camp Fire given their equipment that was in disrepair caused the fires.

Whatever the case, I struggle to invest in a business that is not backstopped by adequate free cash flow, especially when there are other alternatives in the market for a similar valuation that are much less capital intensive. Rather than the base business compounding intrinsic value at an attractive rate, this investment hinges on a one-time valuation multiple re-rating, which may or may not occur.

Consider another heavily regulated, out of favor business in Altria (one of our holdings). Altria trades for about 9x times 2020 earnings against a historical average of 16x, a similar discrepancy as PG&E to peers. Altria generates gobs of free cash flow every year and pays an 8% dividend yield at recent prices. The company is likely to grow at least 3-5% annually for years and in time should re-rate close to a fair valuation. If it doesn’t, the cash still finds its way into investors pockets via dividends, buybacks, and EPS growth. None of that is as apparent (for me) in PG&E’s case because the cash just isn’t there.

My Take

There is no doubt to me that PG&E offers potential solid upside. With the number of catalysts and the current valuation, I think it’s more likely than not that investors do well from here and annual returns could reasonably reach 15-18% for several years. Special situations can be great investments, regardless of business quality, but in our experience the best outcomes arise when catalysts are combined with a fundamentally good company.

The attractive attributes of Berkshire’s energy portfolio – staying in the good graces of regulators, exceptional management, the opportunity to acquire more utilities, and superb capitalization – are not there for PG&E. While tempting, the business quality is not high enough and the uncertainties are too many to warrant an investment for me. This is particularly true relative to other opportunities in which I have more conviction in the likely range of outcomes and risk-adjusted returns.

Disclosure: The author, Eagle Point Capital, or their affiliates may own the securities discussed. This blog is for informational purposes only. Nothing should be construed as investment advice. Please read our Terms and Conditions for further details.